I REALLY AM SORRY for the light posting the last couple of weeks. It’s now officially a rite of Spring – I return to Boston, become surprisingly busy for a spell, and the blogging rate declines to an unacceptably low level. The worst part of this syndrome is that my friends and family, in particular the long suffering Mrs. Soxblog, become the sole recipients of my non-stop and yet annoyingly repetitive analysis of world events. This is an intolerable situation for all concerned – you, me, and especially those who fall into my lair and become a captive audience.

But before returning to current events, I wanted to write a personal essay that hopefully will answer a lot of the questions readers send me and that will also be helpful to a few of you out there.

In 13 months, I’ll be turning 40. I don’t make that statement casually, like most almost-40 year olds do; four years ago, it didn’t look like I would make the milestone, and that if I did make the make the milestone I would do so with someone else’s lungs inside me.

To bring those of you not in the know up to speed, I have Cystic Fibrosis. I was always very healthy for someone with CF until 2002, when my condition suddenly and dramatically changed for the worst. Such turns of fate aren’t uncommon with the disease. By the end of that year, I was on the lung transplant list.

Lung transplants are what medical practitioners refer to as a treatment of last resort. The reason they get such a title is because lung treatments aren’t nearly effective as other organ transplants. The reasons for that fact aren’t really known, but the numbers are sobering. The odds of surviving one year after a lung transplant are 70%. If you make it the one year, you’ve got a 50% of making it five. Statistically, you have only a tiny shot of making it ten.

Thus, lung transplants have won the title of “treatment of last resort” the old fashioned way – they’ve earned it. For obvious reasons, you would have to be a pretty sick puppy to get in line for such a thing.

I don’t mean to pick on lung transplants. If you’re sick enough to warrant one, a potential lung transplant offers the one thing that you probably need the most – hope. Thus, I was excited not only to get on the list, but also to move up it. At one point late last summer, I made it all the way up to number one which meant I had to be accessible at all times to come into the hospital and collect my new organs if and when they became ready.

As I moved up the list, I became excited about having one last finite go at life. I looked at the transplant as a final chance that would give me a few years to get it right. One of the burdens of life is having to plan for a potentially limitless future; most of you are probably wisely socking enough money away in case you live until 100. Me, I didn’t have any such concerns.

I became excited about the prospects of a post-transplant life. According to the people I spoke with, there’s a limited window where after the transplant you feel great, literally better than you have in years. Before your body begins attacking the new organs, life is good indeed.

Because this time period is usually short, I decided that there was no time to lose. Before the transplant, I resolved to do everything possible to get the non-lung portions of my body in as good a shape as possible; I planned to practically spring from the operating room to the basketball courts once I had my new lungs.

I began hitting the gym with more seriousness than I’d had in a decade. I started to rehab my knees, which had been battered by the combination of a lot of running and virtually no maintenance. I even manned up and made frequent trips to the dentist who visited all sorts of depredations on me as a fitting retribution for what he considered a casual approach to flossing.

I considered the working out and the therapy and even the trips to my dentist’s dungeon as training for my transplant. Just like an athlete trains for the Olympics, I would train for the biggest challenge of my life.

A LITTLE OVER A YEAR AGO, I wrote that having a terminal illness is like being at the center of an ever-contracting circle. The circle represents all the things in your life; as you get sicker, the circle contracts and things that were in your life suddenly fall outside the circle. The smaller the circle gets, the smaller the contents of your life get.

While that may initially sound like a grim analogy, trust me, it’s an apt one. Besides, there’s a decided upside to it. At the innermost portions of the circle lays the things that are most important – your heart, your soul, your loved ones. As the circle gets smaller and more and more aspects of your previous life fall outside the circle, what’s really important makes up an ever increasing proportion of what remains. Suddenly, the things that should have always mattered most DO matter most because they’re all that’s left.

That doesn’t mean that having the circle contract is a ton of fun. In retrospect, the enlightenment that came with the circle’s contraction was terrific, but the day I realized I could no longer walk a hilly golf course was a rotten one. There were many such days of similarly painful realizations – none of them were enjoyable.

But something else was happening, too. Although I didn’t realize I was doing so at the time, I began expanding my circle in new ways as my physical abilities eroded. Without being able to spend all my spare hours playing sports (in a decidedly mediocre fashion, mind you) I began focusing on other things. I’d always been an avid reader, but I began reading a lot more. Just today, looking at my Amazon account, I saw I’ve read 119 books in the past year from Amazon alone. I’d be willing to wager I read twice as many as that in 2003.

But most of all, there was the writing. I started blogging in March 2004. I began writing for the Weekly Standard roughly 11 months later. I have found these activities far more rewarding than I anticipated. (Actually, I knew writing for the Standard would be a blast, but the blogging I was less certain of.) They have given me more satisfaction than dropping fly-balls on the softball field ever did. That previous sentence is a flippant way of acknowledging I really can’t express the difference writing has made in my life.

ANYWAY, FINALLY GETTING TO THE POINT, I’ve gotten a lot healthier. The precise reasons for my improvement can’t be scientifically determined – if they could, everyone with end-stage lung disease would have a new Rx.

But I can speculate. I think the promise of the new lungs combined with day-to-day activities that I found meaningful gave me what I’ll tritely refer to as a hope transplant. The introduction of fresh hope to my life in itself made me feel better. The hope plus the working out and doing all the other right things for my condition made me get better in a physically measurable way.

The improvement the past year has been dramatic. My lung function is as good as it’s been in five years. While of course the primary goal, as is always the case where lifting weights is concerned, is to look buff, I tailor my work-outs so they’ll help me function in a day-to-day more effectively manner. While I’ll never run five miles in 33 minutes again (not with these lungs anyway), I can walk across a long parking lot or up a flight of stairs without spending the next three minutes catching my breath. While these might seem like small triumphs, they’re not. Having such abilities makes every day life easier and more pleasant.

So things are good. As you’ve probably figured out, I’m now too healthy to be on the lung transplant list. That’s a good thing. Just between us, I’ve grown attached to these wheezing old lungs and I found the thought of parting with them disquieting. Although still chronically ill, I function a lot better than I have in years. That’s nice.

Four years ago, I didn’t think I’d live to see the Red Sox win the World Series. Against all odds, that worked out for all of us. Actually, a lot of things of even more importance have worked out these past four years.

AND I’VE LEARNED A LOT, TOO. For those of you who are ill or who have loved ones who are ill, here are some of the personal lessons that I’ve taken from my journey:

1) WANTING TO LIVE may be the biggest “x factor” in determining how long you’ll live. For those of you with a serious illness, this is the single most important observation I could share with you. Focus on the reasons that you want to live. Focus on the things that satisfy you – minimize the things that drive you nuts. If you feel your life is endless misery, it will end soon. Fill your days with the activities that make you happy to get out of bed. Eliminate from your days the things you dread. You’ll want to live longer, and you will.

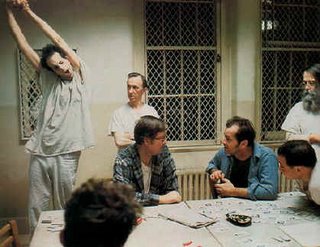

And for those of you with loved ones who you would like to see live for a longer time rather than a shorter time, help them in this. From what I’ve seen in being around other sick people, loved ones can most readily accomplish this by focusing on not being burdensome. I can’t tell you how many seriously ill people I’ve heard say how their family is driving them crazy. Go to a support group meeting, and there’s a 30% chance that part of it will devolve into all the patients pissing and moaning how the people closest to them are driving them nuts. How sad is that?

If you’ve got a gravely ill loved one and you’re driving them nuts, you’ve simply got to find a way to stop doing what’s bugging them. What follows is harsh, but you’ve got to hear it – you’re literally killing them faster.

2) EACH DAY IS A GIFT, although sometimes it is as Tony Soprano says the equivalent of a pair of socks. What I’m really trying to say is tomorrow is guaranteed to no man. No person has gotten off this planet alive. None of us will be the first. Death is part of the deal. Living is pretty great – being seriously ill gives you a visceral appreciation of that fact. And that knowledge tends to make every day, and the little miracles that accompany every day like a glazed chocolate donut or a perfect cup of coffee, all the sweeter.

3) ON A RELATED NOTE, DEATH ISN’T THAT BAD. You look death close in the eye over an extended period of time, and you realize it’s just going to happen. Death will get you, sooner or later. It’s just a fact, and the price of living. One of the things that I’ve been struck by being around gravely ill people is, generally speaking, their lack of fear.

4) DOCTORS ARE GREAT, BUT…First of all, I’ve been blessed with incredible doctors. My CF doctor, in particular, is one of my heroes. He uses his considerable talents to tirelessly serve gravely ill children and young adults. I honestly don’t know how he does it. My only complaint regarding him is that his own life is so admirable, I can’t help but feel like an utter turd in comparison.

But…If your prognosis is imminent death, then by definition your doctors do not have all the answers. If they don’t know how to cure your disease, they don’t understand everything about how it functions. And, for what it’s worth, few doctors are in a rush to confess what they don’t know.

You’ve got to take control. Become an expert on your condition. While your physician will probably always know more about how your disease effects the general population, you know best how your disease is working inside of you. This is your fight – take control of it.

OKAY, ENOUGH ABOUT ME. I’ll be back early tomorrow with an excellent Spanning the Web (if I do say so myself) that’s mostly already written. I think the words “Haditha” and “Murtha”will be prominently featured. As if that weren’t enough, Carl has written an essay on his favorite TV show (no, not “Saved by the Bell – The College Years” as I figured it would be) that I’ll be posting.

Thanks for your patience.

Responses? Thoughts? Please email them to me at soxblog@aol.com